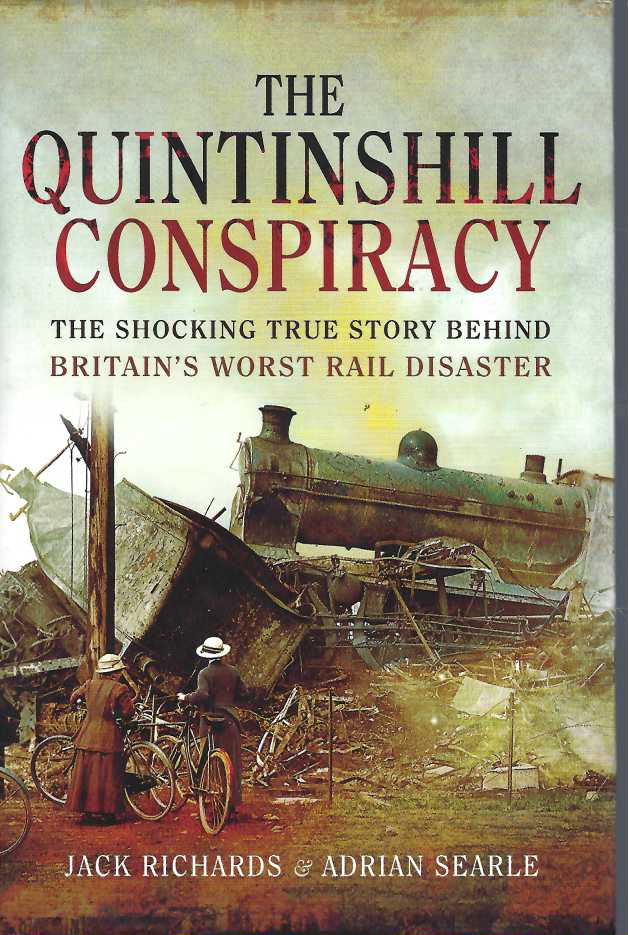

It was the railway’s Titanic. A horrific crash involving five trains in which 230 died and 246 were injured, it remains the worst disaster in the long history of Britain’s rail network.The location was the isolated signal box at Quintinshill, on the Anglo-Scottish border near Gretna; the date, 22 May 1915. Amongst the dead and injured were women and children but most of the casualties were Scottish soldiers on their way to fight in the Gallipoli campaign. Territorials setting off for war on a distant battlefield were to die, not in battle, but on home soil victims, it was said, of serious incompetence and a shoddy regard for procedure in the signal box, resulting in two signalmen being sent to prison. Startling new evidence reveals that the failures which led to the disaster were far more complex and wide-reaching than signalling negligence. Using previously undisclosed documents, the authors have been able to access official records from the time and have uncovered a highly shocking and controversial truth behind what actually happened at Quintinshill and the extraordinary attempts to hide the truth.

pp. 224 illusts #010122

The Quintinshill rail disaster was a multi-train rail crash which occurred on 22 May 1915 outside the Quintinshill signal box near Gretna Green in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. It resulted in the deaths of over 200 people, and is the worst rail disaster in British history.[1]

The Quintinshill signal box controlled two passing loops, one on each side of the double-track Caledonian Main Line linking Glasgow and Carlisle (now part of the West Coast Main Line). At the time of the accident, both passing loops were occupied with goods trains and a northbound local passenger train was standing on the southbound main line.

The first collision occurred when a southbound troop train travelling from Larbert to Liverpool collided with the stationary local train.[2] A minute later the wreckage was struck by a northbound sleeping car express train travelling from London Euston to Glasgow Central. Gas from the Pintsch gas lighting system of the old wooden carriages of the troop train ignited, starting a fire which soon engulfed all five trains.

Only half the soldiers on the troop train survived.[3] Those killed were mainly Territorial soldiers from the 1/7th (Leith) Battalion, the Royal Scots heading for Gallipoli. The precise death toll was never established with confidence as some bodies were never recovered, having been wholly consumed by the fire, and the roll list of the regiment was also destroyed in the fire.[4] The official death toll was 227 (215 soldiers, 9 passengers and three railway employees), but the army later reduced their 215 by one. Not counted in the 227 were four victims thought to be children,[4] but whose remains were never claimed or identified. The soldiers were buried together in a mass grave in Edinburgh’s Rosebank Cemetery, where an annual remembrance is held.

An official inquiry, completed on 17 June 1915 for the Board of Trade, found the cause of the collision to be neglect of the rules by two signalmen. With the northbound loop occupied, the northbound local train had been reversed onto the southbound line to allow passage of two late-running northbound sleepers. Its presence was then overlooked, and the southbound troop train was cleared for passage. As a result, both were charged with manslaughter in England, then convicted of culpable homicide after trial in Scotland; the two terms are broadly equivalent. After they were released from a Scottish jail in 1916, they were re-employed by the railway company, although not as signalmen.

The disaster occurred at Quintinshill signal box, which was an intermediate box in a remote location, sited to control two passing loops, one on each side of the double-track main line of the Caledonian Railway. On that section of the main line between Carlisle and Glasgow, in British railway parlance, Up is towards Carlisle and Down is towards Glasgow. The area around was thinly-populated countryside with scattered farms.

The Ordnance Survey 1:2500 map of 1859 (but not modern maps) shows a house named Quintinshill at approximately 55.0133°N 3.0591°W, around one-half mile (800 m) south-south-east of the signal box. The nearest settlement was Gretna, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to the south of the box, on the Scottish side of the Anglo-Scottish border.

Responsibility for Quintinshill signal box rested with the stationmaster at Gretna station who, on the day of the accident, was Alexander Thorburn. The box was staffed by one signalman, on a shift system. In the mornings, a night-shift signaller would be relieved by the early-shift signaller at 6.00 am. On the day of the disaster, George Meakin was the night signalman, while James Tinsley was to work the early day shift.

At the time of the accident, normal northbound traffic through the section included two overnight sleeping car expresses, from London to Glasgow and Edinburgh respectively, which were due to depart Carlisle at 5.50 am and 6.05 am. They were followed by an all-stations local passenger service from Carlisle to Beattock, which was advertised in the public timetable as departing Carlisle at 6.10 am but which normally departed at 6.17 am. If the sleepers ran late, the local service could not be held back to depart from Carlisle after them, because precedence would then need to be given to the scheduled departure of rival companies’ express trains at 6.30 am and 6.35 am. Also, any late running of the local train would cause knock-on delays to a Moffat to Glasgow and Edinburgh commuter service, with which the stopper connected at Beattock. Therefore, in the event of one or both of the sleepers running late, the stopping train would depart at its advertised time of 6.10 am, and then be shunted at one of the intermediate stations or signal boxes to allow the sleeper(s) to overtake it.[5]

One of the locations where that could take place was Quintinshill, where there were passing loops for both Up and Down lines. If the Down (northbound) loop was occupied, as it was on the morning of the accident, then the northbound local train would be shunted, via a trailing crossover, to the Up (southbound) main line. Although not a preferred method of operation, it was allowed by the rules and was not considered a dangerous manoeuvre, provided the proper precautions were taken. In the six months before the accident, the 6.17 am local train had been shunted at Quintinshill 21 times, and on four of those occasions it had been shunted onto the Up line.[6]

The disaster occurred on the morning of 22 May. On this morning, both of the northbound night expresses were running late, and the northbound local train required to be shunted at Quintinshill, but the Down passing loop was occupied by the 4.50 am goods train from Carlisle. Two southbound trains were also due to pass through the box’s section of track – a special freight train consisting of empty coal wagons, and a special troop train.

With the Down loop occupied, night shift signalman Meakin decided to shunt the local passenger train onto the Up main line. At this point, the southbound empty coal train was standing at the Up Home signal to the north of Quintinshill, and accordingly it was still occupying the section from Kirkpatrick (the next signalbox to the north). This meant that signalman Meakin had not yet telegraphed Kirkpatrick the “train out of section” signal for the empty coal train, which in turn meant that he could not send the “blocking back” signal to advise the Kirkpatrick signalman that the local train was standing on the Up main line.[7] Once the local train had crossed onto the Up main line, Meakin allowed the empty coal wagon train to proceed into the Up loop. Arriving late aboard the local train, the early day shift signalman Tinsley reached Quintinshill signalbox shortly after 6.30 am.[2] At 6.34 am one of the signalmen (it was never established which) gave the “train out of section” bell to Kirkpatrick for the coal train.[8] At this point, two crucial failures in signalling procedure occurred (see Rules breaches).

After being relieved by signalman Tinsley, the night duty signalman Meakin remained in the signalbox reading the newspaper which Tinsley had brought. Both guards from the freight trains had also entered the signal box, and war news in the newspaper was discussed. Shortly afterwards, because the local train had stood on the main line for over three minutes, pursuant to Rule 55 its driver sent fireman George Hutchinson to the box, although he left at 6.46 am, having failed to fully perform the required duties (see Rules breaches).[9]

At 6.38 am the first of the northbound expresses from Carlisle passed Quintinshill safely. At 6.42 am Kirkpatrick “offered” the southbound troop train to Quintinshill. Signalman Tinsley immediately accepted the troop train, and four minutes later he was offered and accepted the second northbound express from Gretna Junction.[10] At 6.47 am Tinsley received the “train entering section” signal from Kirkpatrick for the troop train and offered it forward to Gretna Junction, having forgotten all about the local passenger train (aboard which he had himself arrived that morning), which was occupying the Up line. The troop special was immediately accepted by Gretna Junction, so Tinsley pulled “off” his Up home signal to allow the troop train to run forward.[10]

The troop train collided head on with the stationary local train on the up line at 6.49 am.[11] Just over a minute later, the second northbound express train ran into the wreckage, having passed the Quintinshill Down Distant signal before it could be returned to danger. The wreckage also included the goods train in the down loop and the trucks of the empty coal train in the up loop. At 6.53 am Tinsley sent the “Obstruction Danger” bell signal to both Gretna and Kirkpatrick, stopping all traffic and alerting others to the disaster.[12]

Many men on the troop train were killed as a result of the two collisions, but the disaster was made much worse by a subsequent fire. The great wartime traffic and a shortage of carriages meant that the railway company had to press into service obsolete Great Central Railway stock. These carriages had wooden bodies and frames, with very little crash resistance compared with steel-framed carriages, and were gas-lit using the Pintsch gas system.[13]

The gas was stored in reservoirs slung under the underframe and these ruptured in the collision. Escaping gas was ignited by the coal-burning fires of the engines. The gas reservoirs had been filled before leaving Larbert, and this, combined with the lack of available water, meant that the fire was not extinguished until the morning of the next day, despite the best efforts of railway staff and the Carlisle fire brigade.[14]

The troop train had consisted of 21 vehicles; all were consumed in the fire, apart from the rear six, which had broken away during the impact and rolled back along the line a short distance. The fire also affected four coaches from the express train and some goods wagons.[15] Such was the intensity of the fire that all the coal in the locomotive tenders was consumed.[15]