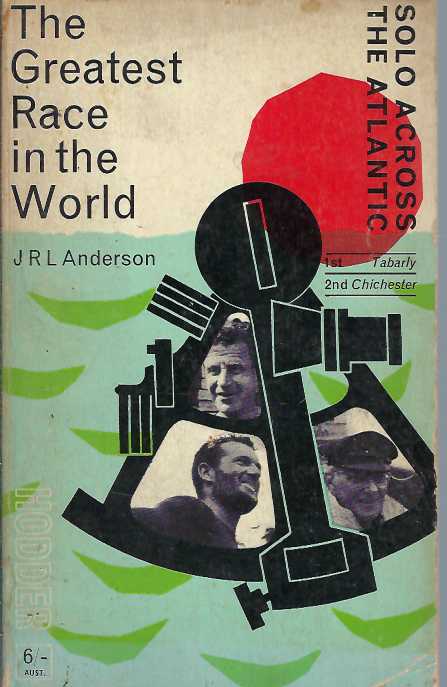

Yacht racing. | Single handed Transatlantic Race, 1964.

pp. 126 illus., ports., map. #0921 Age tanning to sides and pages.

The Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race (STAR) is an east-to-west yacht race across the North Atlantic. When inaugurated in 1960, it was the first single-handed ocean yacht race; it is run from Plymouth to the United States, and has generally been held on a four yearly basis.

1964: Eric Tabarly 1; Francis Chester 2; Val Howells 3

The Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race was conceived by Herbert “Blondie” Hasler in 1956. The whole idea of a single-handed ocean yacht race was a revolutionary concept at the time, as the idea was thought to be extremely impractical; but this was especially true given the adverse conditions of their proposed route — a westward crossing of the north Atlantic Ocean, against the prevailing winds.

Hasler sought sponsorship for a race, but by 1959, no-one had been prepared to back the race. Finally, though, The Observer newspaper provided sponsorship, and in 1960, under the management of the Royal Western Yacht Club of England, the Observer Single-handed Trans-Atlantic Race, or OSTAR, was on.[3][4][5]

The first run of the race was a great success; since then, it has run every four years, and has become firmly established as one of the major events on the yachting calendar. The name of the event has changed several times due to changes in main sponsor; it has been known as the CSTAR, Europe 1 STAR, and the Europe 1 New Man STAR. The professional event has been run as The Transat from 2004, while the race smaller boats is run as the OSTAR. Throughout its history, however, the essentials of the race have remained the same. It has also become known as a testbed for new innovations in yacht racing; many new ideas started out in “the STAR”.

The course of the race is westwards against the prevailing winds of the north Atlantic over a distance of around 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km). The first edition of the race was from Plymouth United Kingdom to New York City; the editions from 1964 to 2000 were sailed from Plymouth to Newport, Rhode Island; the 2004 event sailed from Plymouth to Boston, Massachusetts.[5][6][7]

The actual course steered is the decision of the individual skipper, and the result of the race can hinge on the chosen route:[8]

Rhumb line

The shortest route on paper — i.e. on a Mercator projection chart — is a route which steers a constant compass course, known as the rhumb line route; this is 2,902 nautical miles. This lies between 40 degrees and 50 degrees north, and avoids the most severe weather.

Great circle

The actual shortest route is the great circle route, which is 2,810 nautical miles (5,200 km). This goes significantly farther north; sailors following this route frequently encounter fog and icebergs.

Northern route

It is sometimes possible to avoid headwinds by following a far northern route, north of the great circle and above the track followed by depressions. This is a longer way, though, at 3,130 nautical miles (5,800 km), and places the sailor in greater danger of encountering ice.

Azores route

A “softer” option can be to sail south, close to the Azores, and across the Atlantic along a more southerly latitude. This route can offer calmer reaching winds, but is longer at 3,530 nautical miles (6,540 km); the light and variable winds can also lead to slow progress.

Trade wind route

The most “natural” way to cross the Atlantic westward is to sail south to the trade winds, and then west across the ocean. However, this is the longest route of all, at 4,200 nautical miles (7,780 km).

This variety of routes is one of the factors which makes an east-to-west north Atlantic crossing interesting, as different skippers try different strategies against each other. In practice, though, the winning route is usually somewhere between the great circle and the rhumb line.

The OSTAR, 1964

Thirteen competitors started the next edition of the race in 1964, which by now was firmly established on the racing scene. All of the five original competitors entered, and all five improved their original times; but the show was stolen by French naval officer Éric Tabarly, who entered a custom-built 44-foot (13 m) plywood ketch, Pen Duick II. The days of racers sailing the family boat were numbered following Tabarly’s performance, for which he was awarded the Legion of Honour by president Charles de Gaulle. It is also noteworthy that Tabarly and Jean Lacombe were the only French entrants in this race; Tabarly’s success was instrumental in popularising the sport in France, the country which in future years would come to dominate it.

This was to be the year in which several future trends were established. Multihulls made their first appearance — sailing in the same class as the other boats; and the race featured the use of radio, for the first time, by several competitors who gave daily progress reports to their sponsors.[4][6][11]