MUSIC WEST AUSTRALIANA

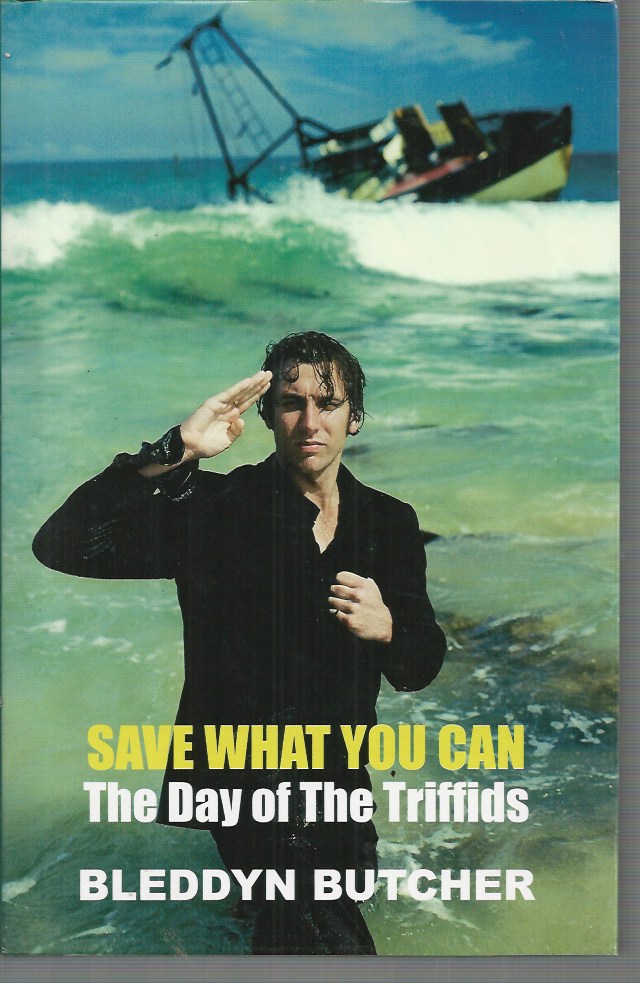

Finally published in 2011 and marking the first full-length account of the band’s history, Save What You Can easily exceeds its lofty expectations and proves well worth the wait. Quite simply, the book evocatively captures McComb from all angles, and should remain the definitive statement on the Triffids for the foreseeable future. Drawing from previous reviews of the band’s work as well as his own interviews with both the group’s members and their inner circle, Butcher grants the reader an intimate portrait of the Triffids, and there is a rhythm to his writing style that makes the book immediately welcoming.

At the center of Butcher’s text is David McComb, the Triffids’ front man and main driving force. To his credit, Butcher’s role as early champion/band photographer/running buddy in the ‘80s does not result in a whitewashed depiction of the singer. Butcher is neither excessively flattering nor condemning; he provides an honest portrayal of McComb as a person. In this way, we see how McComb struggled to cope with relationship troubles – “he was unlucky in love” according to Butcher – and how he was prone to bouts of nightmares, insomnia, short fuses and ugly moods; one girlfriend would categorize him as a split personality. He self-medicated primarily through alcohol – and plenty of other folks in the Triffids’ sphere overindulged – and would later suffer dearly for it. As Butcher says in one of Save’s most poignant passages: “Riotous living takes a heavy toll. So it was with David. Riotous living wasted his substance. It wore out his heart. He fell away.”

Yet McComb was deeply dedicated to songwriting, and it’s this part of his life that serves as one of the central themes of Save What You Can. “A songwriting nut, always on the lookout for ideas. On the scrounge…” is Butcher’s assessment of the Perth native, and he’s right: McComb approached writing with an almost-military degree of discipline, filling reams of notebooks and continually revising his lyrics until they were sharp and piercing. Butcher does a masterful job in showing this side of the musician, especially how he could take events from his daily life, however painful they were, and express them in song. The careful manner in which Butcher traces the genesis of McComb’s songs and offers telling insights into the writer’s creative process is one of the book’s greatest strengths; his examinations of how McComb’s lyrics evolved on tracks like “Field of Glass,” “The Seabirds,” “Monkey on My Back” and “Trick of the Light” are both brilliant and enlightening.

Butcher devotes much of the book to placing McComb’s songs in a biographical context and skillfully dissecting their lyrics, while readily acknowledging that other interpretations are possible. The author does not pretend that everything McComb wrote was lyrical gold. Though lyrical interpretation is a dicey proposition, Butcher’s assertions are well-reasoned and compelling. Most strikingly, he brings a literary sensibility to his study of Born Sandy Devotional and perfectly describes the album in just a few well-written, highly poetic lines: “lone pilgrims and petulant suicides, maudlin confessors, wanton hysterics and brutal dupes…castaway lovers have all washed up in the same place, a desolate spot in a desperate region stretched under a big empty sky.”

Butcher applies his keen photographer’s eye to other facets of the band, particularly in several prosaic sections that recall the dive bars, seedy hotels and miles and miles of bad road that were near-constants as the band crisscrossed Australia and Europe. He covers how each Triffids album was critically received, delves into the various label shenanigans the band dealt with and humorously recounts some of the more ridiculous questions posed to McComb by well-meaning, if entirely clueless, journalists. Any flaws with Save What You Can are minor: the book is written in such a way that assumes the reader has at least a working knowledge of the band and it does not address McComb’s post-Triffids years or the circumstances surrounding his death in 1999, though there is probably enough story there for a separate book.

Ultimately, Butcher argues that the Triffids never really got their rightful due; “It wasn’t enough. Ecstatic reviews did not spark rhapsodic sales. Walls didn’t crumble at trumpets,” he summarizes toward the end of the biography. Save What You Can reportedly took around 10 years to complete, and the care and compassion that went into it are obvious. Plainly stated, it is essential reading for Triffids fans as well as a one-stop primer for anyone who’s just discovering them.

Since the broader recognition of Born Sandy Devotional as one of the great Australian albums, there have been several publications relating to the definitively Western Australian band The Triffids and their singer–songwriter Dave McComb.

This new addition allows us insight into the often tormented creativity of the band’s leader. The Triffids was a band formed out of school friendships and family before settling into its core identity, and was often spoken of as a close-knit group of friends. But there’s a telling moment Butcher documents in the recording of the album Calenture, the band’s first with a major label, when the original (failed) producer replaced band members with session musicians to little opposition from McComb, who for the time being put personal vision and ambition ahead of the band’s collective interest.

McComb is certainly a figure worthy of biography. A superb songwriter, musician and poet, he is especially interesting in terms of how and why his work uses, differs from and interacts with other songwriters and poets of his time (and places). Inevitably Butcher illustrates substance issues as they relate to McComb’s daily creative life, but as this book finishes with the breakup of the McComb version of The Triffids in 1989, we don’t follow the full horrific road to his death in 1999 – drugs are not the prime focus, for which I felt grateful.

In some ways, Butcher comes across as the invisible member of the band. He is silently omnipresent: in the band’s bedrooms and digs, at every performance. His magnificent photographs do capture a curious intimacy, but also seem – or are – clinical, staged and distant. This paradox is at the core of the Butcher–Triffids interaction as manifested in Save What You Can.

Butcher is likely one of the most knowledgeable writers on the Australian music scene of the 1980s. We get insights into the great Go-Betweens and many Perth musicians (such as the Snarski brothers). We see McComb trying to lift himself out of the penumbra of Nick Cave, and inevitably enjoying an eclectic and ever-widening list of musical influences, from Bruce Springsteen to Prince.

Yet the biography frequently risks overindulgence of subject and language. In the effort to capture a zeitgeist – a feeling of the talk, the chat, the life conditions of the band (mainly McComb) in the musical ecology of Western Australia, Australia and, later, Britain and Europe – we become part of a performance, an in situ witnessing that doesn’t always convince.

One man might be at the centre of this book, but all songs are the result of many. The book makes this point, even if at times we get lost in the Dave McComb swirl.

pp. 536, illusts. First Edition SCARCE #240523