Lefroy family. | Western Australia — Genealogy.

SCARCE. 123 p. : ill. ; 26 cm. #0621 Prev ownership whited out on fep. First Edition

Mike Lefroy

I would like to introduce you to some of the characters, from both sides of my family, who made the long voyage from England and Ireland in the mid 1800s to start a new life in Western Australia.

The first of our family to settle here was John Septimus Roe whose daughter Ellen married my maternal great grandfather Augustus Frederick Lee Steere. As the first Surveyor General of the Swan River Colony, arriving with Captain James Stirling in 1829, plenty has been written about Mr Roe and so I will concentrate firstly on my father’s family and the coming of the Lefroys from England and Ireland. But before following them across the oceans and onto what we now know as Bathers Beach, a little background to the Lefroy family.

At the battle of Agincourt on St Crispin’s Day, 1415, a certain Lord de Lovroy led a French rear guard action to cover their withdrawal. He didn’t survive and Henry V, led by his archers, went on to a great victory made famous by William Shakespeare’s play Henry V. It is likely, though there is no conclusive evidence, that this Lord de Lovroy was the ancestor of Antoine L’Offroy from whom all Lefroys throughout the world are descended. 1

Antoine L’Offroy was a Huguenot from Cambrai in the Lowlands, now a town in France near the border with Belgium. As life became increasingly intolerable for Protestants in that region, due to their opposition to the Catholic Church, Antoine with his wife Marie de Hornes fled to England in the 1580s and settled in Canterbury.

By the middle of the 1600s the L’Offroys were entrenched in the silk dyeing industry in Canterbury and doing well. The name Loffroy or Leffroy (the name does not appear to have become fixed until much later) occurs several times in the roll of freemen of the city of Canterbury. But by the middle of the 1700s the only surviving descendent of Antoine L’Offroy was Anthony Lefroy, a merchant banker based in Leghorn or Livorno, a port city on the western edge of Tuscany, Italy. He married Elizabeth Langlois, the daughter of his partner, in 1738 and together they had five children; three of whom survived childhood. Elizabeth Phoebe married Count Medico Staffetti of Carrara and turned Roman Catholic. Unfortunately all further trace of our Italian family has been lost. It is from her two brothers, Anthony Peter and Isaac Peter George, that the two branches of the Lefroy family – the Irish and the English – descend.

Anthony Peter, the ancestor of the Irish branch, joined the army and almost all of his service was spent in Ireland. On his retirement he settled in Limerick.

His brother the Reverend Isaac Peter, the ancestor of the English branch, lived in Ashe in Hampshire. Ashe is near Steventon where a certain Mr Austen was rector. The two families were on intimate terms.

In 1795 Thomas, Anthony Peter’s oldest son, visited his English cousins and stirred the affections of Mr Austen’s daughter Jane. Though the two 20 year olds were certainly attracted to each other there was never a hope of marriage as neither had money. Tom returned to Ireland, eventually becoming Lord Chief Justice and lived to the ripe old age of 93. Jane, moved by her feelings for Tom, began to write perhaps her greatest novel, Pride and Prejudice and went on to become one of English literature’s most widely read and most loved authors. In his old age Tom Lefroy admitted to a nephew that he had been in love with Jane Austen. “It was a boyish love,” he said? The film Becoming Jane (2007) starring Anne Hathaway as Jane and James McAvoy as Tom Lefroy delves in to this boyish love. It is based on a book Becoming Jane Austen by Jon Spence.

Happily in the end the winner was English literature. Tom was off the scene and Jane Austen, who never married, was able to pursue her short but brilliant career.

The first Lefroy to come to Western Australia was Henry Maxwell, a grandson of the Reverend Isaac Peter. It is not clear what motivated him to migrate but it is thought he may have met Captain James Stirling and heard something of the Swan River Colony from him. His purpose originally was to acquire sufficient wealth in Australia to enable him to return and live in England, a motive not unlike the young people today in Western Australia who head north to join the mining boom in the Pilbara.

Henry Maxwell arrived in January 1841 and found conditions totally different from his eager anticipations. It was certainly not a land flowing with milk and honey. The place had not changed much from the early 1830s and the glowing optimism of James Stirling had in many cases turned to homesickness and broken dreams. His earliest existing letter, written in April 1841 to his brother Charles in England, reflected some of his dismay.

A month later though, things were looking up, as Henry Maxwell explained to his mother.

This was his first prediction of Western Australia’s vast mineral resources, one he repeated two decades later after an expedition to the east from York.

By the mid 1840s he had decided that the land was not to his liking and after travelling to the eastern states and South America he returned to England in 1845 where he entered the Royal Navy as an instructor. He resigned from the navy in 1851. In 1853 he married 16-year-old Anne Bate and on Christmas Eve of that year, he left for Western Australia again having been appointed Assistant Superintendent of the penal settlement of the Swan River Colony.

The official duties did not keep him fully occupied and he soon bought land near Fremantle including a 100 acre farm where Beaconsfield TAFE is now located. This expanded into a large operation employing up to 12 men tending 5000 fig trees, 2000 other fruit trees and many vines. Lefroy Road runs through the original property and behind the TAFE College there are what is believed to be some of his original olive trees still growing on the west side of Bruce Lee Reserve.

An old olive tree on the edge of Bruce Lee Oval, Beaconsfield, 2010. One of the few surviving fruit trees from Henry Maxwell Lefroy’s Mulberry Farm established in the 1860s. (Mike Lefroy)

In 1859 he was promoted to Superintendent of the Prison. In 1863 he was granted leave to lead an expedition organized by the Colonial Government and the York Agricultural Society with the purpose of exploring the interior of the colony to the east.

In twelve weeks they travelled nearly 1000 miles. Their journey took them to what was to become the famous goldfields region around Kalgoorlie. He wrote then ‘I think it very probable that in these quartz reefs, gold will be found.’ 5 Sadly, he wasn’t as lucky as Paddy Hannan and his mates three decades later, however Henry Maxwell was on the lookout for pastoral land and following the geological clues was not a priority.

In his detailed notes about the expedition he does point to three recurring themes in the development of Western Australia: the challenges posed by the lack of fresh water, the danger from the build up of salt in the soil and the possibilities of rich mineral resources being discovered.

So for him it was not gold but a large salt lake – Lake Lefroy, to the south of Kalgoorlie – that is the enduring reminder of his trip.

He retired from his position as Prison Superintendent in 1875 and moved back to his property in Russell Street, Fremantle. (This house has been superbly conserved and renovated by local architect Richard Longley who lives there with his wife Kat.)

Just after his retirement from the prison Henry Maxwell wrote to his older brother John Henry who was Governor of Bermuda at the time.

We just had a very exciting event in the escape from the Colony of six of the principal Fenian military prisoners. They were carried off by an American vessel Catalpa, ostensibly a Whaler, but really charted and fitted out by the Fenian headquarters for this special object. The British Government detectives in America had discovered this project, and communicated it to the Foreign Office, which again warned our Governor of it. The latter contented himself with warning the comptroller, who again did nothing whatever to meet and defeat the plot. I guess that both he and the Governor will get a very unpleasant wigging from the Colonial Office later on. 6

He was obviously pleased it didn’t happen on his watch, although if it had been us Irish Lefroys in charge the Fenians would probably have escaped years before!

That brings us to the Irish Lefroys, my direct ancestors, who were the next to arrive in Western Australia.

The two brothers, Anthony O’Grady (my great great grandfather) and Gerald de Courcy, had been visited in Ireland by their cousin Henry Maxwell. Fired up by the prospect of adventure and knowing they had a relative to greet them on arrival, the brothers booked a passage on the Lady Grey and arrived in January 1843. Their arrival was almost a complete disaster. As they approached the shore a bag of 900 gold sovereigns, a gift from an unmarried great grand uncle, slipped from someone’s grasp and disappeared overboard. 7 It was Western Australia’s first recorded ‘bottom of the harbour’ scheme! Luckily the water was quite shallow and a sailor on the boat dived overboard and recovered the bag intact.

The relief at reaching shore was short lived. In a letter to an English cousin nine days after their arrival, Anthony O’Grady wrote:

Our landing in Fremantle was bad – nothing to relieve the eye but white sand in all directions, not grass of any kind what is green, only useless scrub. What a prospect! However I made my way directly to Perth where it is a little better. I found Maxwell had left on an excursion to the interior to seek an inland sea the natives had given some account of. However I had a note from him very kindly asking me to use his house for a month or so. 8

Henry Maxwell had gone on an expedition with a party of Aborigines looking for an inland sea which turned out to be Lake Dumbleyung where Englishman Donald Campbell many years later broke the world water speed record.

Anthony O’Grady and his brother soon learned that for a farmer to survive and prosper they need some sort of ‘off farm’ income (things haven’t really changed in 165 years).

O’Grady’s letter to his cousin also explained the best way to help his father, who had left himself penniless to help he and his brother get ahead, was to get a government position. He went on to observe, ‘There are, I find, situations of 300 pounds per annum, with almost nothing to do, such as Protector of Natives.’ 9

O’Grady went on to ask his cousin if he could have a word in the right places in London to see if a suggestion could be dropped to the then Governor Hutt about a position.

Meanwhile while Maxwell was away the brothers went to York to the Burges family’s property Tipperary where they paid Mr Burges 50 pounds each to gain experience farming under colonial conditions. How fortunate they were to have retrieved their capital from the sea and make a start at farming.

After gaining experience around York, de Courcy set out in search of more land, going via ‘the Priest’s Station’, as Dom Salvado’s newly established mission at New Norcia was then known, and on to Walebing Spring some 20 miles to the north. He was impressed with what he saw and immediately returned to Perth to secure the necessary squatter’s licence. Walebing became the first property to be owned by O’Grady and de Courcy and is still owned and operated by the Lefroy family.

Leasing a property was one thing, making it pay was another and unless one of them could get ‘off farm’ employment they realised they would be in trouble. The situation became so serious the brothers considered packing up and going to New South Wales but the break they were looking for came in December 1849 When O’Grady received an appointment as private secretary to Governor Fitzgerald. From that point on he didn’t look back. He became Colonial Treasurer in 1856, a position he held until 1890 when the colony was granted self-government.

The brothers both married in 1852 – O’Grady to Mary, the third daughter of Captain John Bruce and de Courcy to Elizabeth Brockman daughter of local magistrate William Brockman.

O’Grady and Mary had five children. The oldest, Henry Bruce, followed his father into public service holding various posts including Minister of Education, Agent General for Western Australia in London and Premier from 1917-1919. As a spare time activity he formed a team of Aboriginal cricketers. He captained them from time to time and brought them from the New Norcia Mission to play before big crowds in Perth and Fremantle. 10

In the forest south of New Norcia 1929. Left to right: S Westcott, F Wittenoom, JSB Lefroy, Mollie Lefroy, RB Lefroy. In front RB Lefroy, Sir Henry Lefroy, PB Lefroy. (Photographer EHB Lefroy, private collection)

De Courcy meanwhile pursued a different course to his brother. In 1856, he together with his wife and young family, took a consignment of horses to India for his father-in-law and then travelled on to farm in Ireland before coming back to Western Australia in 1860. He took up land near Bunbury with his wife Elizabeth and growing family, soon to number ten children. The Western Australian climate was obviously good for breeding as two of his sons also had large families. Henry Gerald had fourteen and not to be outdone his brother William Gerald had fifteen.

Sadly De Courcy died in 1877 at the age of 58 as a result of a farming accident when a snake panicked a team of horses he was driving.

From the journey that took them half a world away from home and a shaky start in farming all three Lefroy men, Henry Maxwell, Anthony O’Grady and Gerald de Courcy could look back at their lives in Western Australia with pride. Their sense of adventure and determination is something we that carry on their legacy, can look back on with thanks to lives well lived.

For a woman’s view of Fremantle towards the end of the 1800s it is interesting to look at the life of my great aunt from my mother’s side, Kathleen Laetitia (Kate) O’Connor. When Kate arrived in Fremantle in 1891, she was just 15 and had come from the green and pleasant land of New Zealand. Her father Charles Yelverton O’Connor was an engineer and received a job offer from Premier Forrest that read “Railways, harbours, everything. . .” 11 So the family pulled up roots and headed west.

Kate arrived by ship with her mother, sister and two brothers into the Port of Albany: her father’s harbour in Fremantle would not be opened for another six years and was just a word in his job description at the time. After several months they made their way north by road to join the rest of the family who had arrived earlier and set up house in Fremantle .

Kate’s first impressions of Fremantle were much the same as British author Anthony Trollope who described our town during a visit in 1871 thus:

Fremantle has certainly no natural beauties to recommend it. It is a hot, white, ugly town with a very large prison, a lunatic asylum and a hospital for ancient and worn out convicts. … 12

And there was little in the future that would cause her to change her mind. She became interested in art and in the early 1900s was a student of James WR Linton at the Perth Technical School. But her heart was set on Europe and she never doubted she would one day reach Paris and paint there.

Fifteen years after she arrived in Western Australia, Kate the artist sailed out of her father’s harbour, left Rottnest to port, and eventually arrived in France. There she immersed herself in the Bohemian Paris lifestyle of the artist’s quarter on the Left Bank and apart from brief visits home, didn’t return to Western Australia until after the Second World War.

When she returned from Paris for the last time, Kate found her hometown much as she had left it. She set up a studio at the bottom of Mount Street, Perth and concentrated on still-lifes and portraits. My mother would often collect sunflowers from empty blocks in Fremantle to take for her work. It is ironic that the sandy soil of the town she had little affection for and little trouble leaving produced the colourful subjects for some of her special paintings.

How disappointed Kate must have been returning home to find cafes were restricted to laminex and unimaginative décor behind closed doors. Street eating in Perth and Fremantle until the 1970s was seen as unhealthy and unpleasant. And as for decent cups of coffee – they were nowhere to be found. In an interview with the National Library she admitted wistfully that the Australian landscape held little for her. People-watching in parks and animated conversations in cafes were, for Kate O’Connor, a part of another life and another place. How she would have enjoyed the Cappuccino Strip in Fremantle today. I can imagine her holding court at Gino’s with a table full of Europeans joining her for morning coffee and sharing stories of their countries in pre-war times.

I could sense Aunt Kate was a special person to my mother and that cued my interest in her. To an unworldly 20-year-old from one of the most isolated cities on the globe, Aunt Kate was someone very unusual. To me she represented the exotic world that lay ready to be discovered somewhere west of Rottnest. Looking back I’m sure my mother admired Aunt Kate not just for her passion for art but also her strong will to go against the female conventions of her time – whether represented by duty to husband, or to family, or service to the community.

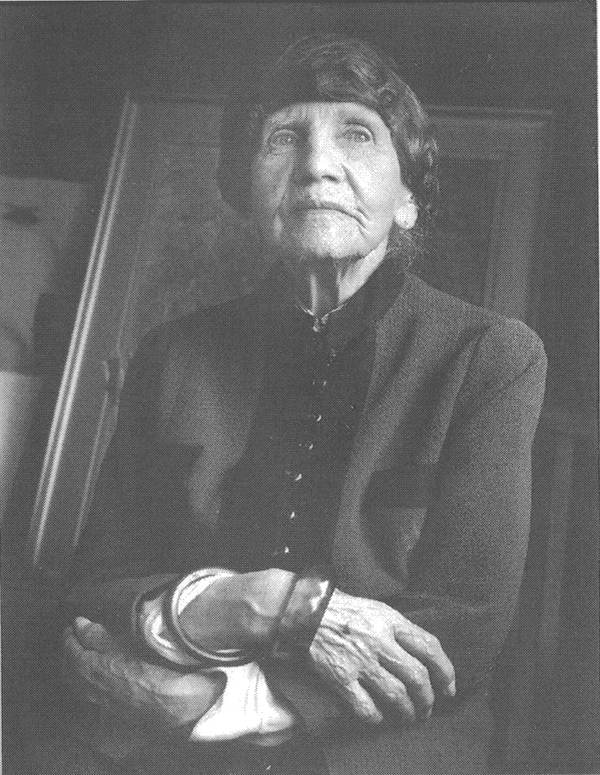

Kathleen (Kate) O’Connor, 1967. (Richard Woldendorp)

Aunt Kate was so different to other adults I had few comparative reference points. Her choice of food was bizarre (“It’s what they eat in Paris,” my mother would explain). Her clothes were, well, different; almost elegant concoctions made from pieces of linen and silk often with a drooping hem and a strategic safety pin to keep things together. Her hats were a feature: in summer they were decorated with artificial daisies and in winter the cherries around the rim would complement the cherry red rouge on each cheek.

Her make-up was cartoonish with her rich rouge cheeks and the odd dab of perfume to make up for her dislike of bathing. My sister Susie remembers the occasional smear of paint on her teeth, a product of holding her brushes in her mouth when in a flourish of creativity. She had gnarled hands collared by large bracelets and long knuckly fingers that had gripped and manipulated paintbrushes and palette knives for many years.

In 1978, ten years after her death, the City of Fremantle accepted a donation of 43 paintings and drawings from Kate’s sister Bridget Lee Steere. It represents the largest holding of paintings by Kathleen O’Connor in an Australian public collection.

Kate had a wicked sense of humour, sometimes too dry and dark for our generation to fully appreciate at the time. It was no doubt nurtured by her father who would offer half a crown to any of the children who came up with a witty comment at the dinner table. Towards the end of her life, her sister Bridget, worried for Kate’s soul, arranged for the Anglican Archbishop to come and visit her. Kate, not to be outdone, promptly arranged for the Catholic equivalent to visit Bridget.

On Tuesdays, in the last few years of her life, my mother would pick up Aunt Kate and bring her home for lunch. In winter she would be seated in the bay window in the study to catch the warmth of the northern light. My mother would bring lunch on a tray – always tripe and champagne. Aunt Kate would gaze out at the street, eating slowly and deliberately, and talk in her husky voice punctuated by a throaty rasp between breaths. When she wanted something and my mother wasn’t there she would lift her wrist and rattle her large bracelets together with a call of “Betty!” that would echo down the hall to the kitchen.

When Kate died she left instructions for her ashes to be scattered at sea. Family stories vary about the exact details but it seems she wanted them scattered in international waters with an easterly wind behind them so they would float away towards Europe. As we speak the ashes are still with us, safe on a mantelpiece in Claremont. While we from time to time wonder what’s best to do with them, she would I’m sure revel in the dilemma she has left behind.

It is now over 40 years since she died and we continue to celebrate her life, which began with a hard landing in Fremantle, but like Henry Maxwell, Anthony O’Grady and Gerald de Courcy Lefroy before her, amounted to much more by the end.

We just have to decide about those ashes.

Fremantle Studies Day, 2008